Last Saturday I experienced my own personal digital divide. At 8:49 am I turned on the computer to work on a blog post and saw this CBC headline on iGoogle: Chile hit by 8.8 earthquake.

Remembering Haiti, where CNN got its updates from social media, I looked at TweetDeck. Many tweets had #chile as hashtags; I set up a feed for that, and then saw several mentioning a tsunami warning for Hawaii (#hitsunami).

My parents, who are in their eighties, are holidaying in Honolulu. My immediate thought: Indonesia, 2004. While my folks are healthy, I’d just as soon they didn’t have to survive a catastrophe while I was cut off from them –not that my being there would have been much help! I knew I couldn’t reach them immediately (the phone lines were busy and they were using an Internet cafe to email).

While I waited, I worked on my digital divide post, and tried to apply some of what I had read to what I was doing online.

I began using Twitter in January (up to that point I thought it silly). Now here I was setting up searches for appropriate hashtags, modifying Tweetdeck, sifting genuine tweets from spam, and using Twitter as my source of real-time information. How did I make this leap? All of the requirements I’d read about in this article (thanks, Natasha) were in place:

- Access (hardware, software, Internet connection, bandwidth) – new laptop, wireless high speed Internet.

- Skill – I was taught well, had been practicing with Twitter, and learning from those I follow. At one point I read this post – “RT @hawaii: Good information on Twitter. Bad information (35 foot waves not likely) and scammers, too. Retweet wisely… #hitsunami” While most people were being helpful, some of the dregs were setting up scam sites to take advantage.

- Policy – No filters restrict my access; I was free to work, to learn, to make my own mistakes.

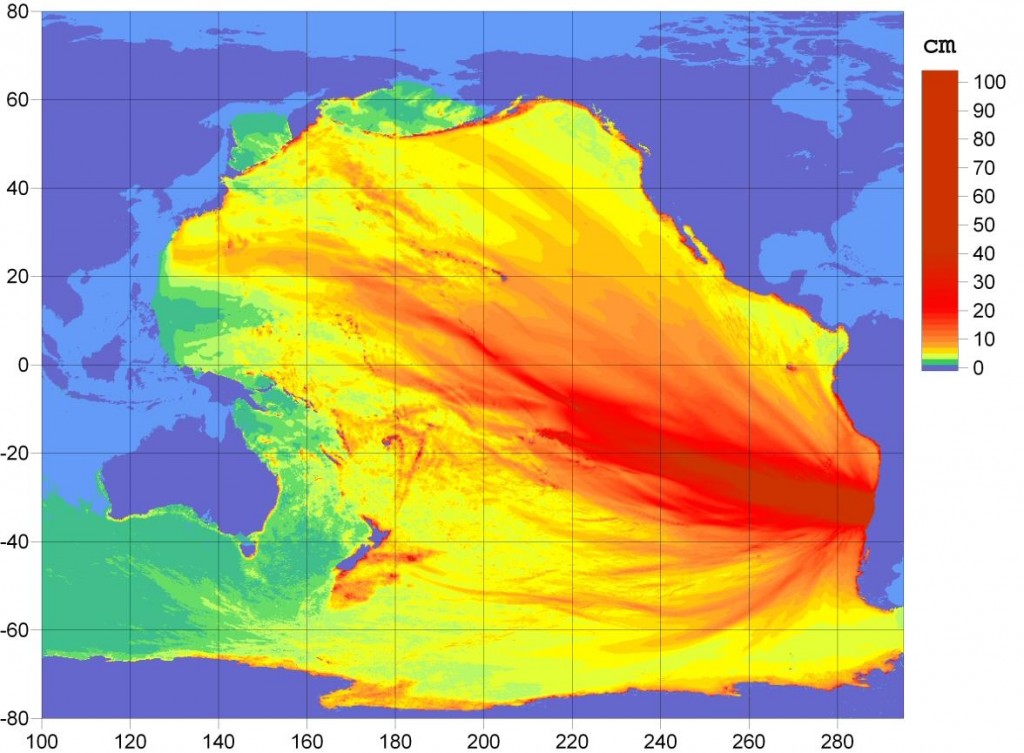

- Motivation – I really wanted to find out what was happening, especially when I saw this image of the energy that might be hitting Hawaii.

Energy dispersal visualization from Chilean earthquake (http://wcatwc.arh.noaa.gov/chile/chileem.jpg)

I wasn’t alone; Wes Fryer posted: “watching #hitsunami TV on ustream along with 75K+ others.” Most worrying, I read: “Next stop #hitsunami . . . 11:35 a.m. Oahu, . . . 9-12 ft. surge estimates.”

As we all know, there was no tsunami. At 5:11 pm Mom emailed to say they were fine — had stayed in their 12th floor room watching the bulletins on TV. While there’s still physical distance between us, the digital gap was bridged.

Time for Educators to “Mind the Gap”

Too often those on the wrong side of the divide watch as others take off into the future. As educators we need to clearly understand what the digital divide is, and its implications for our classrooms and our world.

Wikipedia defines the digital divide as “the gap between people with effective access to digital and information technology and those with very limited or no access at all. It includes the imbalances in physical access to technology as well as the imbalances in resources and skills needed to effectively participate as a digital citizen.”

A number of recent studies have looked at the extent of this divide. Fairlie found that US children with home computers — more whites than Latinos or blacks — are more likely to go to college, and the divide is wider with children than adults.

Digital Divide in Canadian Schools found students from “families with low levels of parental education and those from rural areas are less likely to have a computer in their home. Those from lower SES homes tend to spend less time on the computer and . . . report lower levels of computer competency.”

The report mentions the troubling trend in Alberta to get rid of tls, counsellors, and speech pathologists to free up dollars for technology. As more funding goes to computers, “unequal outcomes may stem from differences between affluent and disadvantaged students in what they do with the technology, once they have access.”

Peña-López points out something that most tls know: access to computers alone doesn’t tranform students into 21st century learners. Competencies are the real concern: “the digital divide in education . . . is not a matter of physical access but a matter of digital skills and how competent students (and teachers) are at computer and Internet usage.”

While Digital Divide in Canada says that while in some ways the divide in Canada is closing, it is still wide between low/high income groups. Obviously factors other than race, funding, and economics come into play. Inequities in filtering (Nelson), attitudes and assumptions about what constitutes effective use of technology (if everyone I know does this, then it must be universal) (boyd), and disabilities also are part of the digital divide.

Vicente and López (2010) present troubling findings about those with disabilities:

- 18% of world population has disability

- Accessibility for people with disabilities neglected by ICT industry

- Rate of internet access for disabled in US half that of regular population

- Many barriers: assistive tech doesn’t work with many web sites

- Assistive tech much more expensive to build and buy

- 80% of people with disabilities worldwide can’t afford proper food, shelter, rehabilitation.

The global digital divide is explored in UNESCO’s Annual World Report 2009. “The digital divide amplifies the already existing social inequalities cumulatively” for economic and social reasons (cost, education), cultural (people have no use for it, no role models), and content reasons (not available in their language, lacking local content). The report highlights the role that culture and regional differences play in how governments choose to develop and implement technology, pointing out that what is appropriate in one area won’t necessarily work elewhere, another lesson that educators must heed.

Bridging the Digital Divide in Our Schools

Access

- Encourage funding to be devoted to people, not just machines.

- Switch to free or open source applications, such as Google docs.

- Use the technology students already posses.

- Thus you free up dollars to provide technology for those students without it at home, or with disabilities.

- Encourage wi-fi sharing so that all have 24/7 access. Provide useful resources on library web site 24/7.

Skills

- Advocate for release/training time for teachers to learn the new technologies/applications themselves, and learn to teach students how to use them.

- Teach students 21st century skills.

- Establish student and teacher mentors.

Policy

- Investigate what works in other schools/districts/provinces but determine information policy based on what your school needs.

- Develop effective acceptable use policies that encourage students to take ownership of their learning;

- Filter effectively.

Motivation

- Develop authentic learning experiences based on what students want and need.

- Do the same for teachers as part of their professional development.

And My Gap?

My parents will be home in a few days (yes!), and I want to teach my dad to use Twitter.

Vicente, M., & López, A. (2010). A Multidimensional Analysis of the Disability Digital Divide: Some Evidence for Internet Use. Information Society, 26(1), 48-64.